Psilocybin Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa: Paris 1959

Henriette B was the first anorexic patient to be treated with psilocybin, with some success

On April 20 1959, Henriette B, a 35-year old woman, an anorexic inpatient at the Centre Hospitalier Sainte-Anne, a psychiatric hospital in Paris, received the first of two intramuscular injections of eight milligrams of psilocybin to treat her anorexia nervosa. She received the second dose on April 24. Anorexia nervosa is one of the most difficult emotional disorders to treat. It is also one of the most lethal because it is conjoined with medical complications: starvation in some cases, suicide in others.

France enjoys the distinction of being the first industrialized country into which psilocybin was introduced to the medical pharmacopeia. This was largely due to the efforts of French mycologist Roger Heim, who from 1952 until 1965 was the Director of the Museum of Natural History, as well as director of the laboratory for the study of mycology and tropical phytopathology at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes.

Prior to the introduction of psilocybin, in the 1950s, doctors in France had begun experimenting with psychedelics as medicine, with LSD.1

The French LSD experiments were psychomimetic studies, little more than observational investigations carried out on unwitting mental hospital inmates, wherein psychiatrists attempted to recreate psychotic states using hallucinogenic drugs. To what end is a matter for speculation. Simply put, the subjects—a majority of whom were women—were treated like lab rats.

The experimental model—such as it was—had no resemblance to the protocols used in psychedelic clinical trials run in the last fifteen years in the US and more recently, in the UK and in Europe. Modern clinical trials require the subjects to take part in a rigorous preparatory process. Set and setting protocols are meticulously followed; and subjects undergo several post-medication integration sessions to make sure they’ve processed the emotional and spiritual experiences they’ve been through. The subject’s humanity is at the center of the process in the recent studies. This was not the case in the 1950s.

Psilocybin became part of the clinical picture in France in 1958 as the result of Dr Heim’s lengthy correspondence with American banker and amateur mycologist Robert Gordon Wasson. Dr Heim and the Museum of Natural History supported and eventually underwrote Wasson’s research. According to his own grandiose retelling, Wasson was the first westerner ever intentionally to eat the sacred mushrooms.

In 1955, Wasson and his wife, pediatrician and amateur ethnomycologist Valentina Pavlovna traveled to Mexico to meet with Mazatec curandera or healer María Sabina2 in the town of Huautla de Jiménez, Mexico. Wasson persuaded María Sabina to let them take part in a velada [healing ceremony], where they ingested Psilocybe caerulescens. Wasson underwent an ecstatic mystical experience, later claiming: “the mushroom holds the key to a mystical union with God.”3 Wasson was able to collect spores, which he brought to Heim in Paris, who successfully cultivated them. Heim sent samples to Albert Hoffman, who, working with Swiss pharma Sandoz, extracted the active component, psilocin, in 1958.

Vincent Verroust, Historian of Science, Centre Alexandre-Koyré, School of Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences, in Paris; and the Institute of Humanities in Medicine, Hospital of the University of Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland described what happened next:

“[Heim] arranged for the substance to be tested quickly at the Sainte-Anne hospital in Paris. At this hospital, under the supervision of Professor Jean Delay, clinical trials were carried out on 29 healthy volunteers and also on 72 mentally ill patients.”

Thus in 1958, the first study with psilocybin was initiated under the supervision of Dr Jean Delay, President of the Faculty of Medicine, assisted by, among others, Dr Anne-Marie Quétin, who documented the story of Henriette B in her doctoral dissertation: “La Psilocybine en psychiatrie clinique et expérimentale (1960).”4 A total of 101 subjects participated, some willingly, and some oblivious to the kind of medications they were being given.

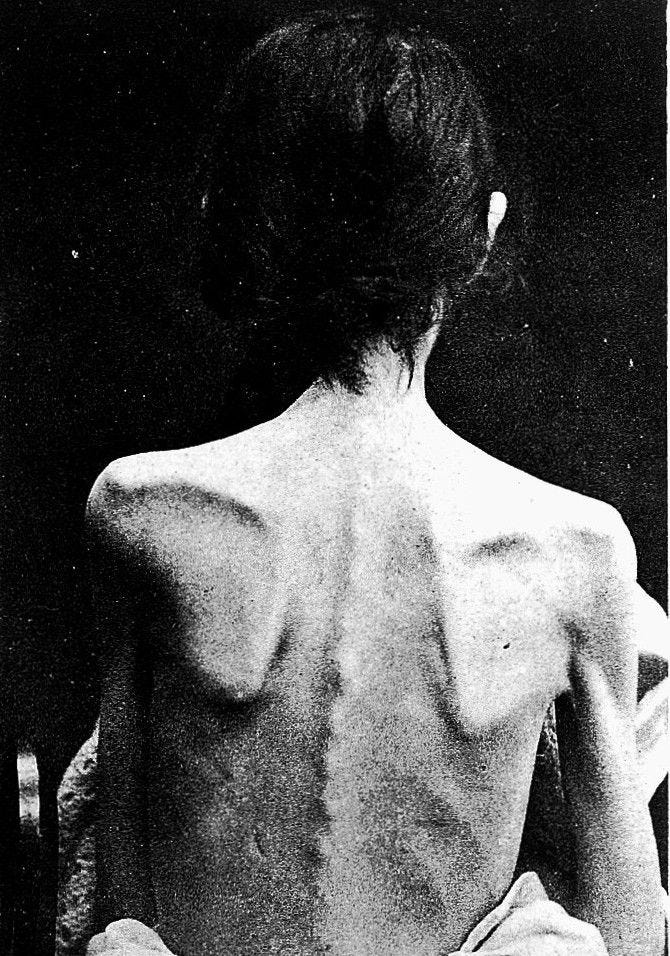

Unlike many of the patients who were treated with psilocybin, Henriette B came into the clinic voluntarily. At 35, Henriette B lived with her parents, and worked as a skilled worker [her specific trade isn’t specified]. It was not her first hospitalization for anorexia. She was hospitalized in 1943, then again in 1952, 1956, and 1959. When she arrived at the hospital, she weighed 40 kilograms – 88 pounds. She measured 1 metre 60 cm in height (5 foot 6 1/2 inches tall.) Dr Quétin describes Henriette B in her dissertation: “Her way of living [with her parents] strikes us with its extreme regularity: everything is timed and scheduled. She is permitted no distractions except those that are considered cultural.”5 Quetin notes also: “The family millieu is dominated by a hyperactive and and perfectionistic mother.” Henriette B rationalizes her behavior – her inability to eat— with the words: “I cannot afford satisfaction freely without feeling an immediate sense of guilt.” She speaks of a “spiritual craving” in the same language she uses for a craving for food. She hopes one day for a future where she will finally be liberated from “a body she could never accept.”

Henriette B’s first dose of psilocybin didn’t produce any immediate changes, because, as was noted after the fact, she’d been treated with chlorpromazine (later known as “the chemical lobotomy.”)

The following day, however, Henriette B reported that during the afternoon, she’d felt euphoric, she felt like dancing, and she felt lightness, as though she didn’t have any feet. She reported the impression of being disincarnate, of having nothing but a soul, of being in paradise.

Dr Quétin and her colleagues decided to carry out the second phase of the experiment without the chlorpromazine. Henriette B was given no chlorpromazine for three days prior to her next dose. On 24 April, she was again injected with 8 milligrams of psilocybin.

Things progressed very differently.

Twenty-five minutes after the injection, Henriette B reported she had “no notion of time” and “my gestures seem to be slowed down.” A little later, she felt nauseated. After an hour, she began to cry: “You’ve left me alone,” followed by anguish: “I saw the agony of Christ. I lived it with him.” She described suffering from an absence of affection, even from her teachers. “I am reproached for being not very open.” She recalled being abandoned by a caretaker when she was young. She went on to describe her family, her mother was extremely authoritarian, her father an intellectual, her sister very pretty and very chic. She laughed and she cried, at one point declaring: “It’s the way of the cross you’re making me take. I’m in the clouds.”

The session lasted about three hours. According to the report, Henriette B was agitated during the night.

The second session was followed by a remarkable improvement in Henriette B’s symptoms. She was able to recall her experiences with precision. Moreover, there was a kind of mood reversal. She was euphoric; and she began immediately to gain weight.

Dr Quétin described the difference between the two drug trials as very instructive. The second, in particular, she notes in the absence of “treatment” with chlorpromazine, allowed for an influx of memories. “Without any control, and with extreme violence, she revealed that she considered the origins of her illness mostly as the result of her grievances against her mother. As for her memories of childhood, up to then forgotten, she relived them emotionally, in particular her separation from the person she considered as a second and actual mother (which explains a period of anorexia as a child).” She goes on: “During the following weeks, Henriette B returned to her regular life. Unfortunately, however, the favourable effect didn’t persist in the long term; and eventually, again at home, Henriette B became depressed once again.”6

Henriette B’s experience was the most remarkably positive of the 101 subjects studied. But given the absence of follow up treatment—integrative sessions, for instance—the fact that her progress coudn’t be sustained isn’t surprising. Nor is the fact that psychedelic medicine was abandoned altogether in France within the next two years. That story will be told in a subsequent newsletter.

In August, 2019, Roland Griffiths, PhD announced the inception of the first contemporary anorexia nervosa study with a call for participants “ages 18 - 65 with anorexia nervosa to participate in a research study looking at the effects of psilocybin, a naturally occurring psychoactive substance found in certain species of mushrooms. The study will investigate psychological effects of psilocybin, including whether or not it can help with anorexia.”

Having participated in a psilocybin clinical trial at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine under Dr Griffith’s supervision myself in 2012, I suspect the long-term results of this new anorexia study will be more fruitful.

LSD was synthesized in Basel, Switzerland by Albert Hoffman from ergot, an alkaloid-producing fungus that grows on rye. Hoffman discovered its psychoactive properties accidentally when he ingested a few grains, and envisioned “an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures.”

Lutkajtis, A. (2020). Lost Saints: Desacralization, Spiritual Abuse and Magic Mushrooms. Fieldwork in Religion, 14(2), 118–139. https://doi.org/10.1558/firn.40554

ibid

Quétin, Anne-Marie (1960). La Psilocybine en Psychiatrie Clinique et Experimentale. (Thesis for the Doctorate in Medicine State Certification.) Presented and publicly supported 10 June 1960. Faculty of Medicine, Paris.

ibid p 134

ibid p 139